Sectigo’s CodeGuard is Sharing the Files From Their Customers’ WordPress Websites With Third-Parties

Making backups of WordPress websites is an important security measure, but it can also create security risks of its own. That too often comes in the form of security vulnerabilities that are in backup plugins, where even plugins with millions of installs can be failing to implement basic security. It turns out that can also come from a third-party you are paying to handle doing backups for you.

Recently there was news coverage of a tool that claimed to detect “malicious plugins” and a research paper about it, titled, “Mistrust Plugins You Must: A Large-Scale Study Of Malicious Plugins In WordPress Marketplaces“. The research is odd, since it is mixing together plugins that apparently contained malicious code when they were added to websites and malicious code that was added to plugins after a hacker had gotten access to websites. The latter is an odd thing to focus on, since once hackers have gained access to websites, they often plant malicious code in various places on the website. That really has nothing to do with WordPress plugins, since the same code could in other files on the websites as well.

What we were more interested in is where the samples used for the research came from. A story from The Hacker News was oddly silent on that. Looking at the research paper provided a troubling explanation. The answer was that the backup provider CodeGuard, which is owned by Sectigo, provided the researchers with their customer’s WordPress websites’ files:

Our collaboration with CodeGuard furnished access to the nightly backups of over 400K unique WordPress websites. These backups contain the server-side files and their version-controlled changes collected from July 2012 to July 2020. They give YODA the vantage point of both an individual website owner as well as a hosting provider (i.e., access to the webserver files). This allows us to retroactively deploy YODA over 8 years by executing YODA on each nightly backup for every website. Note that CodeGuard anonymized the website owner profiles — only a random ID and the URL were linked to each website backup. Furthermore, we only analyzed the webserver files with no database access. All websites in our study are CodeGuard’s active clients, i.e., if a client stops using CodeGuard’s service all their data is immediately deleted, thus we will not have access to it.

The files on the website can contain sensitive information that shouldn’t be shared with third-party like this without explicit consent from the website’s owners, which isn’t what happened here:

However, all of CodeGuard’s customers agree to their

Privacy Policy whereby their data may be shared with

third-parties to help CodeGuard safeguard their

websites.

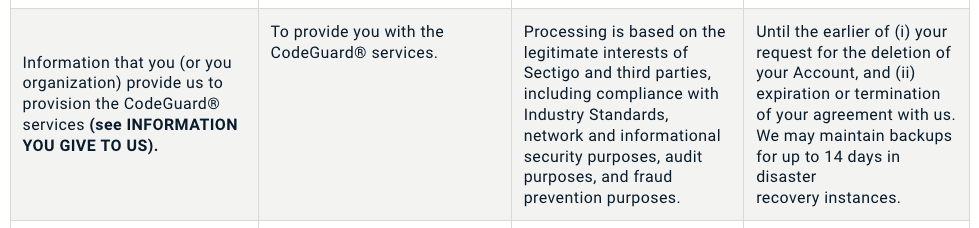

Looking at the privacy policy linked to CodeGuard’s website, this appears to be the relevant portion:

That disclosure doesn’t seem to make it clear that what went on here could happen:

Processing is based on the legitimate interests of Sectigo and third parties, including compliance with Industry Standards, network and informational security purposes, audit purposes, and fraud prevention purposes.

With every WordPress website, one file will contain the database login credentials for the website, so even if CodeGuard didn’t provide someone with database access, they would have the login credentials needed for accessing it.

If a WordPress plugin allowed someone other than the administrator of the website access to arbitrary files, that would be a serious vulnerability, so what happened here should be treated the same.

CodeGuard isn’t the only party that engaged in highly questionable behavior here, as the Georgia Institute of Technology thought it appropriate to get access to files they shouldn’t have had without explicit consent.