Cutting Through Wordfence’s FUD on Millions of Attack Attempts Against WordPress Websites

It isn’t uncommon to see comments online from people scared after a WordPress security solution, say, the Wordfence Security plugin, has alerted them that the solution has blocked a large amount of hacking attempts. The best advice as to what they should do in that situation is to a) ignore the alerts and b) find a new solution that isn’t trying to scare them through fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD). To get a better idea of why that is, let’s look at a recent blog post from the aforementioned Wordfence.

Inaccurate Vulnerability Information

In a post titled Holiday Attack Spikes Target Ancient Vulnerabilities and Hidden Webshells, Wordfence claimed that hackers were targeting a vulnerability in a plugin named Downloads Manager (not to be confused with Download Manager):

There were two spikes specifically targeting the Downloads Manager plugin by Giulio Ganci.

The claimed information about the vulnerability supposedly targeted is not correct. Here is what they wrote:

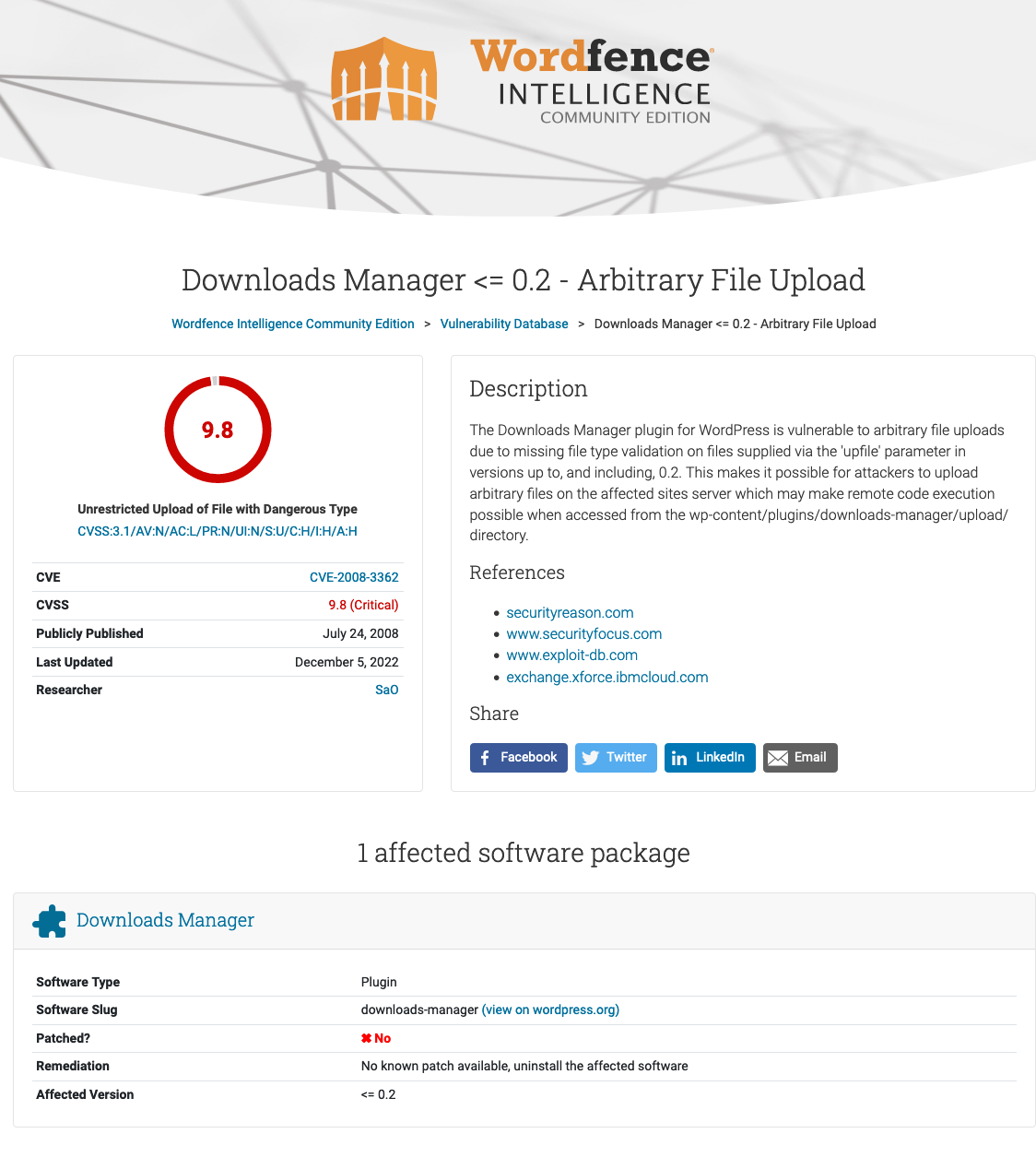

The vulnerability would-be attackers are attempting to exploit is an arbitrary file upload vulnerability found in Downloads Manager <= 0.2. A lack of adequate validation made it possible for files to be uploaded and run on a vulnerable website. This could lead to remote code execution on some sites. The vulnerability was publicly published in 2008, and was never patched. The plugin has since been closed and is no longer available.

If you look at the details of that claimed vulnerability, it involves sending requests to a file named upload.php in the root directory of the plugin. But the first version of that plugin in the WordPress plugin directory, 1.0 Beta, doesn’t contain that file. Either there are two different plugins being conflated or that file was removed before the plugin made it in to the WordPress plugin directory. It appears that the author of the post was parroting incorrect information from Wordfence’s plugin vulnerability data set (which has a lot of problems):

The plugin was closed on the plugin directory in 2016, after we saw a hacker probing for it and found a different arbitrary file upload vulnerability in the plugin. It’s unclear from the information mentioned in their post, which of these vulnerabilities were being targeted.

Details Missing

As to the attacks, they made this claim:

The first spike was on December 24, 2022, with a second spike on January 4, 2023. In the 30-day reporting period, only 17 attempts to scan for readme.txt or debug.log files did not target the Downloads Manager plugin. On average, the rule that blocks these scans typically blocks an average of 7,515,876 scan attempts per day. The first spike saw 92,546,995 scan attempts, and the second spike soared to 118,780,958 scan attempts in a single day.

What is missing there are a couple of critical details to assess the threat from those attacks.

The first detail missing is how many websites were being targeted. Either this type of attack is successful the first time or it isn’t. That result won’t change if it is tried again. So multiple attempts don’t cause any additional risk to the website. It is just a hacker wasting resources.

According to WordPress’s stats, the Wordfence Security plugin has 4+ million installs, so somewhere between 4 and 5 million installs. To keep things simple, let’s assume that there are 4 million installs of the plugin and every website with it installed had at least one attempt by the hacker. On the day they recorded the most attempts, that would amount to nearly 30 attempts per website.

If the website doesn’t have the plugin installed, Wordfence would be claiming to have blocked 30 attacks, which would have failed even without their plugin installed.

Another way of looking at that, is that on that day, if every website had that plugin installed, at best the hacking attempt could have had a success rate of 3.3% (since additional attacks would not have led to a hacked website being hacked again). That is a pretty low success rate, but that is assuming that they all had it installed, which isn’t the case. So how many websites are even using the plugin? Wordfence didn’t say. When you know what the number might be, it isn’t hard to guess why.

WordPress doesn’t say how many installs a closed plugin has, as can be seen with this plugin. A good reason for doing that is that it would hide from hackers which known vulnerable plugins are the best targets. A bad reason for doing that is that it allows WordPress to hide how many websites they are leaving vulnerable as they refuse to warn that WordPress websites are using known vulnerable plugins.

The last record for the plugin’s page in archive.org before it was closed was in August 2016 and shows that the plugin had 1,000+ installs at the time. So somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 installs. The previous record had it at 2,000+ installs.

If there were still 2,000 installs of the plugin now, which there likely are not, and each of those were targeted on the day with the most attacks attempts Wordfence recorded, the success rate of the hacking attempts would be 0.0001%.

One way to look at that is that hackers will reach far to hack a few websites. Another is that hackers are often not that competent, since the success rate of these hacking attempts would be abysmal and there are likely more effective uses for the resources utilized.

Security providers have an interest in making hackers sound scarier than they really are as it both helps to sell security solutions, but also get them off the hook when those solutions fail to deliver on the promised protection.

Keeping Plugins Up to Date Doesn’t Address This

Before claiming that the vulnerability being targeted hadn’t been fixed, the author of the post, Topher Tebow, wrote this:

What they have in common is that the best defenses are proactively securing your website and keeping WordPress core, themes, and plugins updated.

That is contradicted by then claiming that the vulnerability hadn’t been fixed (despite it actually having been fixed).

You have to wonder about the quality of other Wordfence employees, if this is someone allowed to be a public voice of the company.

FUD Free Security

There are a couple of key takeaways from looking closer at this, as to how to avoid FUD when presenting hacking attempts blocked by WordPress security solutions.

The first is to not emphasize a total number of attempts blocked, as blocking repeated attempts that would have, at best succeeded, once, isn’t meaningful information.

The second is to delineate between attacks that could have possibly succeeded and those that couldn’t. Here it would be easy to check if the plugin is installed. If it isn’t, then the attack couldn’t have succeeded and that can be noted.

With our own firewall plugin, we have from the first version intentionally not emphasized attacks attempts blocked, since it isn’t a secret that they are not a good measure of the security being provided and likely to cause unnecessary concern. We recently integrated data on what plugins are connected with exploit attempts logged by the plugin, to provide better information for those reviewing logged attacks about the security risk connected with attempts blocked.